The Collection

Campaign for Governor of Pennsylvania (1978)

Extent: 85 linear feet

“The opportunity to run for governor in one's home state comes to few people in their lifetime, and I was understandably intrigued by the possibility [considering] my longtime interest in public service” (Evidence draft, p. 259). And so it was that upon returning to Pittsburgh in March 1977, following the two years in Washington serving as assistant attorney general in charge of the Criminal Division, Thornburgh set out to seek Pennsylvania’s governorship in the following year’s election. With the generous encouragement of his law firm, Kirkpatrick, Lockhart, Johnson, & Hutchison, which he rejoined, the balance of 1977 was spent assessing his chances.

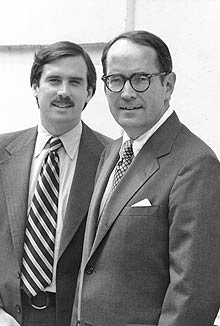

A state the size of Pennsylvania is a daunting challenge to statewide candidates. Major hurdles were the financing required and the all-important campaign staff and organization. Thornburgh was lucky in having a college classmate, Evans Rose Jr., who actually enjoyed fund-raising and who successfully did so for this campaign and many other endeavors to follow. His choice of Jay Waldman as campaign manager was what Thornburgh describes as a “leap of faith.” His “savvy intelligence and strategic insights ... [and] absolute loyalty” (Evidence, p. 76) proved to be remarkable then and over the years that followed. By fall, the hard-core campaign organization also included Paul Critchlow, a former political writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer, as press secretary; Rick Stafford, a graduate of Carnegie Mellon’s Graduate School of Urban Affairs, to head the research team; Jim Seif, who first helped with the 1966 campaign for U.S. Congress, to take on scheduling; and Murray Dickman, a classmate of Stafford’s, described by Thornburgh as “our utility infielder” (Evidence, p. 76). These names resound throughout the files from this successful campaign, as well as for the years as governor, and ongoing.

The primary election effort included accepting virtually all speaking invitations extended; testifying before a state House subcommittee on crime and corruption in the [Governor] Shapp administration; meeting with GOP leaders around the commonwealth; and attending festivals, GOP picnics with new “Thornburgh for Governor” buttons, county dinners, and candidate forums. There was always the hope for increasing press coverage for this lesser-known candidate, whose odds in 1977 were twenty to one.

The official kickoff of the campaign came on a snowy Pittsburgh day, January 10, 1978, which was followed by a three-day blitz of the state. Thornburgh’s remarks reviewed the unfortunate number of criminal convictions or other wrongdoing of state officials, and further noted: “It is a time for state government to learn to live within its means. ... We must recognize that there are limits to our resources. We cannot try to do everything lest we do all things badly. We must do those things which are important and do them well” (Evidence, p. 81). All campaign speeches and position papers are available here online.

By the time of the primary election on May 16, 1978, Thornburgh was one of five principal Republican candidates. These were: Pennsylvania State House leader Robert Butera of Montgomery County; Pennsylvania Senate leader Henry Hager of Williamsport; former Philadelphia District Attorney Arlen Specter; and David Marston, former U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. The two “fringe candidates” (Evidence, p. 82) were: Andrew Watson, former chair of the state’s Constitutional Party; and Alvin Joseph Jacobson. A series of detailed and meticulously researched position papers were released, endorsements began to proliferate, but at the last, the consensus was that the primary election was “too close to call.”

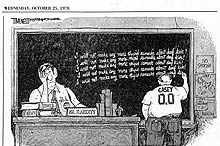

It was not until after two o'clock in the morning after the primary that victory was declared and William W. Scranton III was found to hold the number two spot on the Republican ticket. On the Democrat side the victors were Pete Flaherty, popular former Pittsburgh mayor, and the “improbable Robert P. Casey, the Pittsburgh schoolteacher who soon became known, with our assistance, as ‘the wrong Bob Casey’” (Evidence, p. 85).

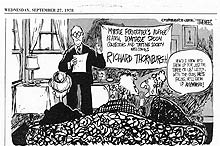

As the general election got under way, the comprehensive Bob Teeter poll conducted after the primary showed Flaherty with a 32-point lead—55 percent to 23 percent! This stunned the campaign, which knew Thornburgh was the underdog, but not by such an almost insurmountable deficit. Flaherty was described as an “easygoing, unassuming former Pittsburgh mayor whose cost-cutting measure had included ‘turning in the mayor’s Cadillac for a Dodge’ [and Thornburgh was seen as] the ‘steely-eyed prosecutor ... big time crime buster ... [and] cold-blooded crusader’” (Evidence, p. 89). Hard work was ahead as the campaign entered the summer of 1978 and schedulers booked Thornburgh everywhere they could. There were long days of breakfasts, luncheons, dinners, picnics, rallies, news conferences, editorial board meetings, and one-on-one sessions. “Ginny and I confided that our bottom-line goal was simply to avoid a humiliating defeat” (Evidence, p. 90).

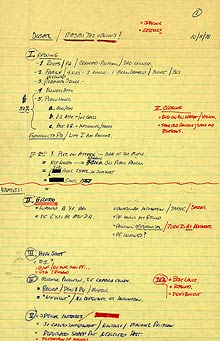

However, Jay Waldman presented to Dick Thornburgh, on July 7, a “strategic campaign plan that we were to follow to victory” (Evidence, p. 90), one embracing an “Eastern [Pennsylvania] strategy.” This was scrupulously followed as the campaign slowly but surely gathered major endorsements, Thornburgh became increasingly recognized in voter-rich Eastern Pennsylvania, his carefully researched and strategic issues found their marks, and Flaherty’s cost-cutting image came under question: “Did Flaherty save Pittsburgh, or bring it to its knees?”

As the underdog, Thornburgh had agitated for debates and agreed upon two dates in the fall. Needless to say the stakes were high as the election neared and Thornburgh’s research team prepared a massive binder of responses to every question that might conceivably be raised. Also included are likely responses of Flaherty and Thornburgh’s potential responses to even those, all of which are included in the collection, for both debates.

On October 10, the date the first debate was taped, “Flaherty surprised everyone by appearing in his shirtsleeves, apparently to enhance his ‘man of the people’ image ... our team was, on the whole, satisfied with the outcome. Most stories identified [Thornburgh] as the aggressor and highlighted Flaherty’s admission regarding tax increases” (Evidence, p. 96).

Meanwhile the candidates for lieutenant governor were coming under scrutiny. Bill Scranton was out on the campaign trail, well informed, and serving as a real asset to the election efforts. Democrat Bob Casey, the Pittsburgh schoolteacher, with precisely the same name as the auditor general who sought primary selection as candidate for governor, was creating major controversy for the Flaherty campaign: “’Like what do we need special teachers for the hearing-disabled. Put those kids at the front of the classroom if they can’t hear’” (Evidence, p. 97).

A significant endorsement came from the Philadelphia Daily News on October 25, the date of the second debate. “Flaherty wore his suit coat this time ... no new ground was broken ... [and] as one observer noted: ‘Overall, we would guess that Thornburgh gained the most from the televised debate. ... Most viewers probably were impressed by Thornburgh’s ease and confidence as he presented his arguments’” (Evidence draft, p. 314).

Best of all was the postdebate news that the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette had endorsed the Thornburgh/Scranton ticket and two days later, “the new Gallup poll showed that the margin among likely voters had shrunk to 4 percent—Flaherty 49 percent, Thornburgh 45” (Evidence, p. 97). Momentum was further evident, on October 29, by a “triple play” with all three of the remaining newspapers in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia endorsing Thornburgh/Scranton. By the beginning of November, Thornburgh/Scranton had twenty-five newspaper endorsements from across Pennsylvania, and Flaherty had only two. All the endorsements, for both tickets, are included in the archive and serve as a fascinating account of the campaigns and the candidates as Election Day neared.

“As the campaign drew to a close, Ginny and I shared a plane back to Pittsburgh with reporters Tom Ferrick Jr. from the Philadelphia Inquirer and Bob Dvorchak from The Associated Press. Both had been with us through thick and thin. ... I asked them who they expected to win. One of them replied, ‘Well, you’ve run a helluva race. You’ve made up a lot of ground and given Pete a real run for his money. But I don’t think you’re going to make it.’ ‘That’s about how I see it,’ I responded. But Ginny and I knew how far we had come and hoped against hope that we could pull off a victory” (Evidence, p. 99).

Anticipating a long election night wait, the news at 8:30 p.m. that “Walter Cronkite has just called you a winner” dumbfounded Thornburgh as he dressed at home. The family was gathered for the trip to campaign election headquarters, where “pandemonium reigned. By 9:30, all three networks had called the election in our favor, and at 10:35, Pete Flaherty called to concede and offer his congratulations. ... The dimensions of the victory were astonishing ... [and] our upset captured a good deal of national attention” (Evidence, p. 100).

In addition to the campaign documents and ephemera, there are detailed files in the collection regarding the vigorous postelection transition period, directed by Rick Stafford. Not only was there the matter of careful selection of the cabinet, in itself a challenging task, but also the opportunity to create study teams to assess issues, problems, and needs in the various departments of state government. The study team reports are included in the collection and provide significant insight into priority areas identified for the new administration.

The inaugural plans and events are fully documented in the collection and include a video of the inauguration that is available here online. Thornburgh’s inaugural address, he states, “was to be the most important that I had ever delivered and I spent an uncommon amount of time preparing it” (Evidence draft, p. 333).

Thornburgh further states, “I set out what I felt to be the ‘spirit of Pennsylvania.’ ... While I noted ‘a saddening loss of belief in the ability of government and its leaders to serve the people,’ I stated that people wanted to believe in their government. What was needed, I said, was ‘strong, effective, and forthright leadership.’ This I promised to provide, together with hard work, integrity, frugality, and ‘a sense of humanity that is blind to race and roots, to sex and color, but is mindful of political injustice and human need’” (Evidence, p. 104).

There are twelve sections of detailed campaign files: "Speeches and Testimony"; "News Releases"; "Endorsements, Responses, and Articles"; "Campaign in Progress"; "Issue Research"; "Opposition Research"; "Planning Documents and Memoranda"; "Campaign Name Files"; "Dickman Staff Files and Polls"; "Candidate Thornburgh’s Files"; "Chron Files and News Clippings"; and "Transition and Inaugural."

Of special interest to researchers will be the five scrapbooks assembled after the campaign, which track it in content as well as in the media. These were undertaken at the request of the candidate, immediately postelection, and, in fact, contain some material not available elsewhere, particularly some staff notes and memoranda. These are both colorful and informative and include issues, media coverage, internal campaign staff comments, and notes, as well as campaign ephemera. These scrapbooks have been reformatted for preservation purposes. All collection scrapbooks are enumerated in Section 21 here.